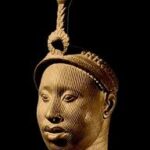

Yoruba Abobaku: What You Need to Know About The Tradition of “He who Dies with the king”Abobaku

Yoruba Abobaku: What You Need to Know About The Tradition of “He who Dies with the king”Abobaku

Origin and Role

Approximately 400 years ago, in the Old Oyo Empire, the role of the Abobaku held significant importance. The term “Abobaku” translates to “He who dies with the king,” referring to an individual chosen to be buried alive with the king upon the monarch’s death. It was believed that the failure to inter the Abobaku with the king would result in severe misfortune for the people. This unique practice was specific to the Old Oyo Empire and did not extend to other Yoruba regions such as Ile-Ife.

Purpose

The Abobaku tradition served as a form of insurance for the Alaafin, the king of Oyo. It ensured a strong, permanent bond of allegiance between the king and his most dependable general. The Abobaku was highly motivated to keep the king alive, as his own life was directly linked to the monarch’s. Historians suggest that this practice emerged as a countermeasure against the frequent poisoning of kings by their successors and palace workers, creating a deterrent to such treachery.

Historical Context

The custom of the Abobaku dates back to the ancient Oyo Empire, known for its powerful rulers who exerted great control over many villages. The Oyo Empire’s dominance often led other towns to seek independence, especially during times of war. During these turbulent periods, the Abobaku, often serving as a war general, was responsible for the king’s safety during battles and was expected to die protecting the Alaafin. For instance, when Alaafin Atiba, the first Alaafin of the old Oyo Empire, passed away, over 21 people were buried alive with him.

Change and Abolition

The tradition persisted until relatively recent times. When a king died in 1980, preceding Olubuse II, there was no Abobaku to be buried with him, yet no calamity befell the land after seven days, challenging the necessity of the practice.

During the colonial era, the arrival of British colonial masters brought significant changes. The Abobaku, who became an essential interpreter for the British, was too valuable to be sacrificed. When a king died, the British authorities protected the Abobaku by framing him for a crime and sentencing him to life imprisonment, thus preventing his burial with the king. On the sixth day, palace chiefs, realizing the Abobaku was unavailable, decided to use a live cow as a substitute, and surprisingly, no disaster occurred. This incident led to the abolition of the Abobaku tradition.

Legacy

The abolition of the Abobaku practice marked a significant cultural shift in Yorubaland. It illustrated the adaptability of Yoruba traditions and the influence of colonial intervention. The saying “eni oyinbo feran ni ti mole” (whoever the white man loves is being caged) reflects the paradox of colonial influence—while it often disrupted traditional practices, it also provided protection and new opportunities for some individuals within society.

TRENDING SONGS

WOMAN REVEALS HOW PATIENCE AND TIMING HELPED HER BUILD A PEACEFUL FIVE-YEAR MARRIAGE

WOMAN REVEALS HOW PATIENCE AND TIMING HELPED HER BUILD A PEACEFUL FIVE-YEAR MARRIAGE

How N100m Was Mistakenly Paid Into Egbetokun’s Son’s Personal Account — FPRO

How N100m Was Mistakenly Paid Into Egbetokun’s Son’s Personal Account — FPRO

RCCG PASTOR ANGRY OVER CALLING Him“MR” INSTEAD OF “DR,” DECLARES CURSE ONLINE

RCCG PASTOR ANGRY OVER CALLING Him“MR” INSTEAD OF “DR,” DECLARES CURSE ONLINE

NPMA Appeals to Nigerian Government for Compensation After Lagos Market Fire

NPMA Appeals to Nigerian Government for Compensation After Lagos Market Fire

Rest Every Four Hours, FRSC Issues Safety Guide for Fasting Motorists

Rest Every Four Hours, FRSC Issues Safety Guide for Fasting Motorists

NNPC Boss Ojulari Bags UK Energy Institute Fellowship

NNPC Boss Ojulari Bags UK Energy Institute Fellowship

Shock in Anambra: Bride Disappears Moments Before Wedding

Shock in Anambra: Bride Disappears Moments Before Wedding

Nigerian Woman Returns ₦330 Million Accidentally Credited to Her Account

Nigerian Woman Returns ₦330 Million Accidentally Credited to Her Account

APC Don Reach Morocco?’ VeryDarkMan Reacts to Seyi Tinubu Poster

APC Don Reach Morocco?’ VeryDarkMan Reacts to Seyi Tinubu Poster

Bride Breaks Down in Tears as Wedding Meals Were Kept Secretly While Guests Go Home Hungry

Bride Breaks Down in Tears as Wedding Meals Were Kept Secretly While Guests Go Home Hungry

Share this post with your friends on ![]()